Trace Minerals

WHAT ARE TRACE MINERALS?

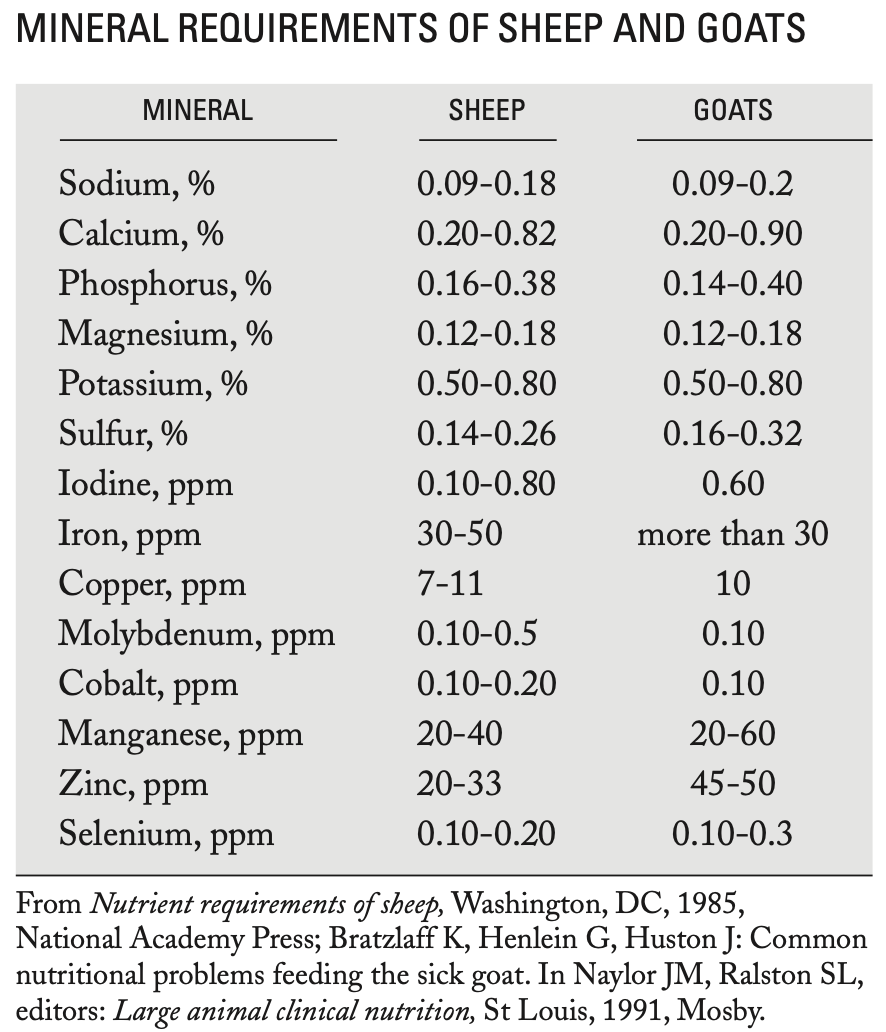

There are two main categories of essential minerals - “macro-minerals” and “micro-minerals,” also called “trace minerals.” There are seven macro-minerals: calcium, phosphorus, sodium, chloride, magnesium, potassium, and sulfur. They make up a larger portion of an animal’s diet. There are eight trace minerals: copper, molybdenum, cobalt, iron, iodine, zinc, manganese, and selenium. These trace minerals only make up a small percentage of an animal’s diet.

Animals primarily acquire macro minerals and trace minerals through their diet (forage and other feedstuffs). These diets are typically deficient in trace minerals, though, and require supplementation. Animals have a natural drive to consume macrominerals, protein, and energy when they are deficient, so deficiency in macrominerals is much less common than deficiency in trace minerals.

One or more trace minerals are required for virtually all biochemical processes in the body, so deficiencies tend to cause a wide range of diseases. There are also complex interactions between these trace minerals so deficiency (or surplus) in one trace mineral can affect others.

Below is an overview of each of the trace minerals and some diseases they cause when deficient; however, it is important to remember that even though these are outlined individually, these minerals have complex interactions between themselves and within the body.

IRON

Iron is found in all cells of the body, but has a major role in red blood cells. The animal’s bloodstream accounts for about 2/3 of their total iron in their body. Animals get their iron from their diet; however, they have difficulty eliminating excess iron, which is then stored in the liver.

Animals are born with minimal iron stores, so the main source of iron for baby animals is colostrum, followed by milk. They also consume iron in the soil and from their mom’s feces. Iron deficiency in baby animals is rare and we typically only see it if the animal is fed an inappropriate diet or kept off soil (like production piglets raised on concrete).

Anemia

In adult animals, iron deficiency is usually caused by anemia (low red blood cells). The most common cause of anemia in sheep and goats is internal parasites, specifically The Barber Pole Worm.

COPPER

Copper is required for the proper development of bone, cartilage, tendons, nerves, and melanin (for dark coat colors). Since it is so essential for early development, deficiencies in copper usually cause clinical signs in young, growing animals when copper requirements are highest.

There are two main causes of copper deficiency: consuming diets that are deficient in copper or consuming diets that are excessive in substances that block copper absorption, like sulfur, molybdenum, and iron. These substances bind to copper in the animal’s rumen, preventing uptake into the animal’s bloodstream.

Enzootic Ataxia - “Sway Back”

Typically seen at birth when a kid or lamb is born to a copper-deficient mom. The baby is weak, unable to stand, shaking, and head nodding. They typically can still see and nurse, so if you have a baby that is too weak to nurse it is most likely a different cause (like low blood sugar) rather than copper deficiency.

Older kids and lambs can also become copper-deficient if they are fed a deficient diet. These older babies are typically very weak in their back end.

Once these signs are seen, treatment is typically not successful. Preventing this disease in the first place by making sure pregnant females have adequate copper supplementation while pregnant and when lactating is the best strategy.

Wool & Coat Problems

In adults, a deficiency in copper with cause dulling of their coat. Without copper, the enzyme that creates dark pigment cannot function, which leads to a lightening of the animal’s hair or wool and diminishes the quality of the fiber. Typically, you will see weight loss and unthriftiness as well if your animal’s dull coat is due to copper deficiency.

SELENIUM

Selenium deficiency is caused by the consumption of forages grown on selenium-deficient soil (like here in Northern California). Selenium is essential for many processes in the animal’s body, so a deficiency can cause a wide range of diseases, including poor growth, decreased milk production, and impaired immune systems.

White Muscle Disease

White Muscle Disease (Nutritional Muscular Dystrophy) is the most common disease associated with selenium deficiency. Deficiency causes damage to the animal’s muscles, mainly their most active muscles, targeting mainly the leg muscles, heart, and tongue (in baby animals nursing). Depending on which muscles are affected, there can be a wide range of clinical signs from weakness or a stiff gait, difficulty nursing, or even sudden death. Diagnosis can be made with a necropsy (animal autopsy) to identify the characteristic white streaks in the heart or leg muscles.

ZINC

Zinc is required for thousands of biochemical reactions in the body. Because of this, a deficiency in zinc causes a wide range of clinical diseases - poor growth, skin problems, feet/hoof problems, and reproductive issues. The main issue with zinc is its bioavailability (the animal’s ability to absorb and use the zinc) in diets and supplements. Diets high in calcium and phosphorus (like alfalfa or cereal grains), can block the absorption of zinc by the body. Also, many supplements have a type of zinc that is poorly absorbed by animals. You want to make sure your trace mineral supplement has zinc methionine.

Zinc Responsive Dermatosis

Some animals deficient in zinc will have grey, rough, flaky skin - usually around their eyes, nose, and feet. This condition usually resolves once more zinc is added to their diet.

OTHER TRACE MINERALS

Iodine

Iodine is absorbed by the thyroid gland and is essential for thyroid hormone production. Both iodine deficiency and excess can lead to the development of a “goiter” (swelling of the thyroid gland). If seen, please seek veterinary advice.

Molybdenum

Deficiency of molybdenum is not usually a concern; however, excess can block absorption of copper, leading to copper deficiency. Ideally, you want a diet that has six times as much copper as molybdenum. Diets that have less than two times as much copper as molybdenum can lead to signs of copper deficiency.

Cobalt

Dietary supplementation of cobalt is a unique nutritional requirement of ruminants. It is used in the rumen to generate vitamin B12. Deficiency in Cobalt is extremely rare and does not usually manifest as a clinical disease.

Manganese

Manganese is necessary for the normal development of bone and reproductive processes. Deficiency is Manganese is incredibly rare.

TRACE MINERAL SUPPLEMENTATION

Free-Choice

Free-choice minerals are typically provided to your animals in the form of blocks or loose sand. Studies have shown that animals prefer loose minerals and consume 2-7 times the amount compared to the blocks.

It is important to provide a balanced trace mineral product rather than buying the trace minerals individually and relying on the animal to select and eat what they need. Salt concentration is actually the driver of consumption of trace minerals (not deficiency in a specific mineral!), so offering separated trace minerals (also called “a mineral buffet”) can lead to further deficiency and even mineral toxicities.

The downside to providing free choice minerals is you do not know exactly what each any animal is consuming. It’s recommended to weigh the trace minerals you set out beforehand then weigh what your animals leave behind. This gives you an idea of the total amount they have consumed, but it is on average for the herd, not the individual animal.

Boluses

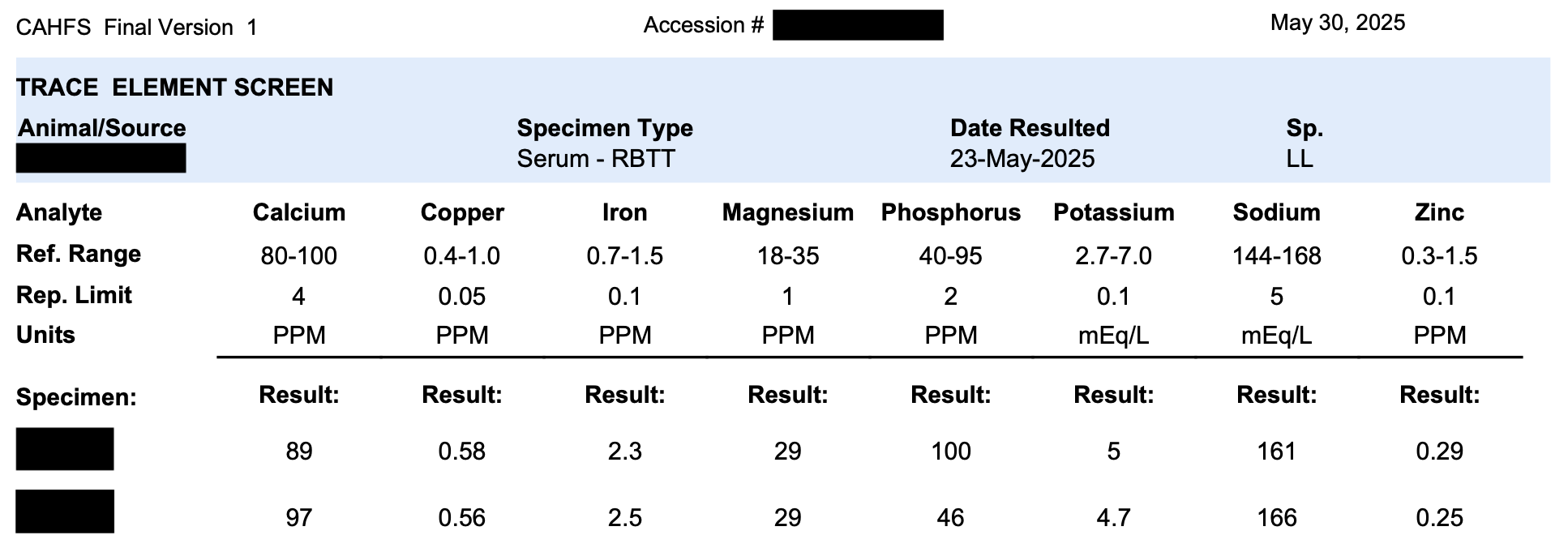

Slow-release boluses are helpful when you need to dose a specific animal, especially for copper deficiency. You want to confirm the copper deficiency in your animal with testing (see below) before treating because signs of copper deficiency are non-specific (dull coat color, weight loss, weakness etc.), and you can easily cause copper toxicity, which can be fatal, if you supplement an animal that doesn’t need it.

Copper bolus needles are much more effective than copper oxide powder because the oxide powder has poor “bioavailability” - the animal’s ability to absorb and use the trace mineral.

Injectable

Injectable trace mineral products (Bo-Se, Multimin, Iron Dextrans, etc.) are another option for supplementation. The upside of these is that you know the exact amount that each animal is getting. They also work quickly to provide supplementation to that animal. However, studies have shown that they have a minimal effect in animals that are not deficient (why testing is so important!), and overuse and overdosing of these injectables can lead to toxicity and even death. So the upside is that injectable trace minerals provide the deficient animal with the trace mineral they need quickly; however, they provide little to no benefit in animals with adequate trace mineral status.

TESTING TRACE MINERAL LEVELS

Severe trace mineral deficiencies are rare in the US today, but we often see marginal trace mineral deficiencies, which have more subtle clinical signs. If you are seeing poor hair coat, weight loss, poor performance, or poor reproductive performance in your animals, you may want to consider testing your trace mineral levels. Consult with your veterinarian further if you are concerned your animals may be deficient in trace minerals.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

It is important to realize that one or more trace minerals are required for virtually all biochemical processes in the body, which leads to a wide range of clinical signs when deficiency is present. There are several options for supplementing trace minerals in animals; however, a good quality loose trace mineral designed specifically for your species of animal is the best place to start. If you are concerned that your animal is experiencing trace mineral deficiency, consulting with a veterinarian and testing the animal if needed, is the best next step to getting their minerals balanced and back to a healthy life.

References

Gould, L., & Kendall, N. R. (2011). Role of the rumen in copper and thiomolybdate absorption. Nutrition Research Reviews, 24(2), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954422411000059

Raisbeck, M. F. (2020). Selenosis in ruminants. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 36(3), 775–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2020.08.013

Pugh, D. G., & Baird, N. (Nice). (2012). Sheep & Goat Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Smith, M. C., & Sherman, D. M. (n.d.). Goat medicine. Wiley-Blackwell.

Smith, B. P., C., V. M. D., & Pusterla, N. (2020). Large Animal Internal Medicine. Elsevier.

Swecker Jr, W. S., & Van Saun, R. J. (2023). Trace minerals in ruminants. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 39(3), i. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0720(23)00069-5

Related Resources

Journal article with images of sheep skin disorders caused by deficiency in zinc, copper, and vitamin A