The Barber Pole Worm

Effective parasite control is essential for keeping your sheep and goats healthy. This guide will focus on the most important parasite causing clinical disease in sheep flocks and goat herds – the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus).

While there are many other parasites out there, the barber pole worm causes the most severe disease in your adult animals, and prevention and appropriate treatment of the barber pole worm is the cornerstone of a successful parasite management strategy. This guide will walk you through how to identify symptoms, implement pasture and herd management strategies, and choose the right treatments, all while minimizing the risk of drug resistance and long-term negative health impacts on your animals.

There is a lot of information here that goes in depth into the “why” of these strategies, so at the end, there is an example treatment plan that condenses it down to the “how” for your use. Parasite management needs to be tailored to individual circumstances and can become very complicated and confusing, so if you have any questions, you can always reach out to your veterinarian for further guidance and recommendations for your herd or flock.

THE BARBER POLE WORM

Knowing your enemy is crucial to defeating them. Understanding how the barber pole worm lives, breeds, and infects your animal is essential to properly prevent infections and treat them when they occur.

Where it Lives & Eats

The barber pole worm is a parasitic nematode (roundworm) that infects the abomasum - the “true stomach” of the ruminant. The abomasum is one of their “four stomachs” (rumen, omasum, and reticulum being the other three). Adult worms attach to the lining of the abomasum and suck blood from the animal. It gets its name from its red and white spiral pattern resembling a barber’s pole. This pattern is actually caused by the blood-filled intestines wrapped around the worm’s white reproductive tract.

Lifecycle

The adult worms lay thousands of eggs daily inside the animal’s abomasum. These eggs are passed through the feces and infect your pasture. The eggs need warm, moist environments to develop and hatch into larvae. These larvae are then ingested by your animals while grazing. The larvae mature in the animal’s abomasum and becomes a blood sucking adult. The time from ingestion of the larvae in the pasture to a blood-sucking egg-laying adult usually takes about 2-3 weeks. This means that pastures can become heavily contaminated with this parasite very quickly if not properly managed.

SIGNS OF DISEASE

The barber pole worm is a bloodsucking parasite and causes severe anemia in sheep and goats. Clinical signs of barber pole infection are directly related to signs of blood loss:

Signs of Blood Loss (Anemia)

Pale mucous membranes (see FAMACHA scoring below)

Bottle jaw (fluid swelling under the jaw due to low blood protein)

Lethargy / Weakness

Weight loss (see body condition scoring BCS below)

Poor growth

Sudden death (with severe infection)

Dark / tarry feces (from abomasal ulcer bleeding)

Not Diarrhea

It is important to realize that the barber pole worm alone does not cause diarrhea in sheep and goats. Diarrhea can be a sign of internal parasites in adult animals, but it is typically another cause, like rumen acidosis, diet change, Johne’s disease, etc. Young animals’ diarrhea (less than 8 months of age) is typically caused by coccidia (look for a future post discussing prevention and treatment of this parasite).

PASTURE MANAGEMENT

With any parasite problem, prevention is much more effective, less labor-intensive, and cheaper than treatment. Targeting the barber pole worm’s lifecycle and preventing infections from happening in the first place is the best strategy for keeping your animals healthy.

Rotating Pasture

You want to manage your pasture in a way that prevents the barber pole worm’s lifecycle from completing. Your animal needs to ingest the larvae stage (L3) of the parasite in the grass in order to become infected so making an environment that prevents eggs from hatching will stop infections from happening in the first place.

The worm needs a moist pasture to grow from an egg to the infective larvae stage, so the good news is that for half the year in Northern California, most eggs passed in the environment will die before reaching the infective larvae stage (unless you are irrigating your pasture). During the rainy, winter months is when you need to be most worried about reinfection.

Dividing up your pasture into sections and rotating your animals through those sections prevents over-grazing and allows for pasture sections to rest. You want to allow enough time (at least 60-90 days during wet weather months) to allow the larvae to die off. For example, you can divide your pasture into three sections and rotate every 6-8 weeks. This will allow 12-16 weeks before the animals return to the first pasture.

Preventing Over-Grazing

You want to avoid overgrazing because the larvae live in the bottom 2” of grass (typically where it is the right temperature and wetter). If you leave your grass higher this will allow the sheep and goats to eat the tops without being exposed to the larvae. Letting your animals out into the pasture later in the day can also help reduce their exposure because the larvae tend to retreat deeper down into the base of the grass during the hottest part of the afternoon.

If your stocking density is too high, this can lead to over-grazing. Consider moving your animals to a larger area or decreasing the total number of animals you have.

“Vacuuming” with Other Species

Rotating other animals that are not susceptible to the barber pole worm (like cattle and horses) through your pastures can help “clean up” the parasites. These species are not clinically affected by the barber pole worm so they can graze and eat the larvae, killing them without getting sick.

PREVENTING PARASITE EGGS

Identifying and Removing High Shedders (the “Typhoid Mary’s”)

The barber pole worm is capable of shedding 5,000-10,000 eggs per day. This means they can contaminate your pasture very quickly. The good news is that there are typically only a few animals in your herd that are responsible for shedding 80% or more of the eggs in your pasture.

Sheep and goats have individual, genetically linked susceptibility to the barber pole worm, so it is important to identify which of your animals (if any) have clinical signs of parasites (high FAMACHA scores, low BCS - see below). The animals with clinical signs of barber pole infection are typically the animals that are shedding high levels of eggs in the pasture and you should consider removing them from your pasture. “Removal” can be culling (if acceptable with your management practices) or isolating in their own area to prevent infecting others. You can house them with other species that are not affected by the barber pole worm (horses, cows) to keep them company. Also, keep in mind that individual susceptibility is a genetic trait, so if you are breeding animals, animals that are clinically sick with barber pole worm should not be used in your breeding program.

Quarantine and Test New Additions

Do a fecal test alongside your biosecurity blood testing on all new additions (CAE, CL, Johne’s). Keep them isolated for 10-14 days and monitor for other concerning signs of illness – nasal discharge, sneezing, diarrhea, etc.

If they are shedding parasites on a fecal test, you will want to do a FECRT (see instructions below) to ensure your dewormer is effective and they clear the parasite before introducing them to your animals.

Remember, there is individual susceptibility to the barber pole worm and if you new animal is consistently shedding high levels of parasites despite dewormer, this animal is not safe to add to your herd or flock.

FIGHTING INFECTIONS

Even if with the most diligent pasture management strategies, your animals are going to be exposed to parasites. This itself is not a bad thing, and almost all animals live normal, healthy lives with some degree of internal parasites. What is cause for concern is when these animals become ill, that is when treatment is warranted (see treatment below). Animals that are provided high-quality forage and nutritional support are the best equipped to deal with internal parasites and prevent illness.

Protein

Your sheep and goats need to be healthy with a well-functioning immune system to fight these parasites off. Ensuring they have adequate protein in their diet and trace minerals (like zinc) are important for their overall immune health. Providing feed higher in protein, like alfalfa or grain (not for neutered males – see “Preventing Urolithiasis”) can help increase their ability to fight off barber pole worm.

Trace Minerals

You should always provide trace minerals designed specifically for your species. These come in a block or loose form, typically animals prefer the loose form. If you are concerned that your animals are deficient in one or more trace minerals, blood panels can be performed by your veterinarian to assess their status.

DECIDING WHO TO TREAT

Why can’t I just deworm everyone?

It is very important not to treat all of your animals. This will lead to resistance by selectively killing all the worms in your pasture that the dewormer is effective at killing. Since we only have three classes of dewormer on the market, and resistance is already very widespread, contributing to this issue by deworming all your animals at once can potentially create a worm that we will not be able to treat.

It is important to only treat animals that are clinically affected by the parasite. These animals are not only the ones that are sick and warrant treatment, they are also typically the animals that are shedding the most eggs into the environment – reducing the number of eggs reduces the number of infected animals.

You want to evaluate your animals routinely (typically monthly or a few days before you move them to a new pasture) and make note of their body condition score and level of anemia (called FAMACHA scoring). We recommend keeping diligent written records so you can identify trends and animals with chronic issues.

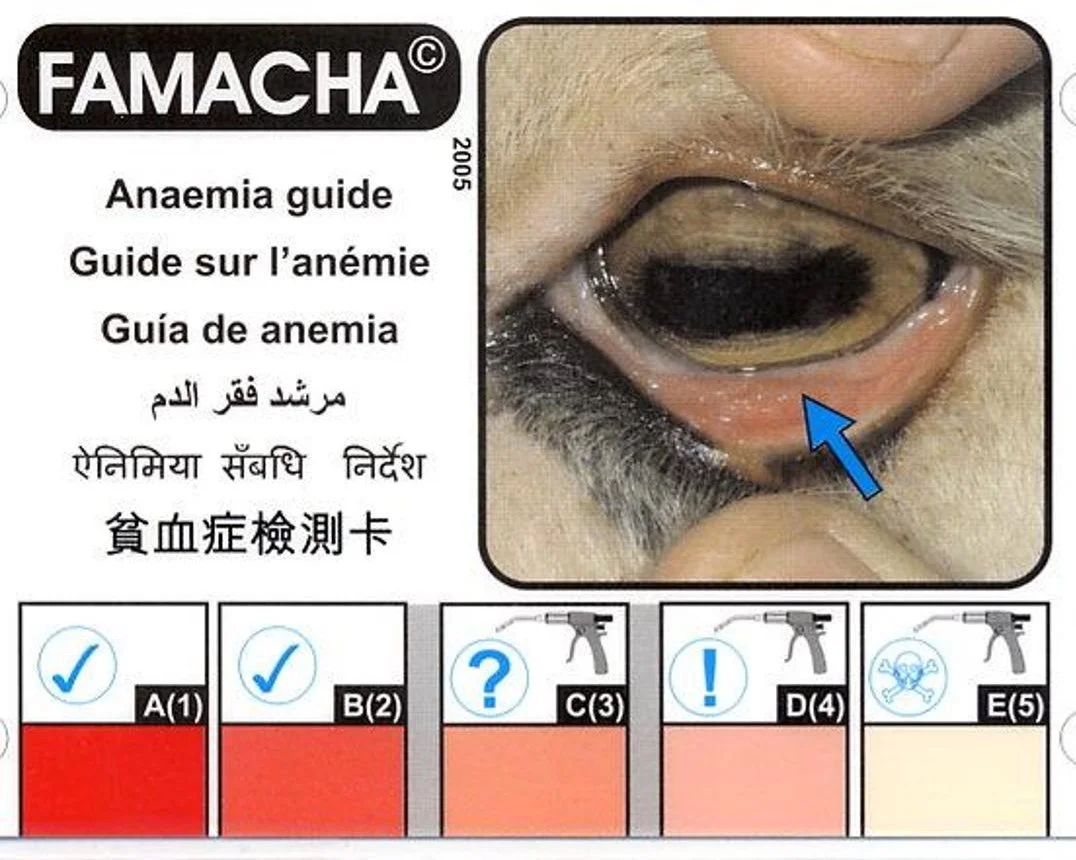

FAMACHA Scoring

FAMACHA scoring is a way of evaluating your animal’s level of anemia (low red blood cells). Since the magnitude of barber pole infection directly relates to the level of anemia they cause in the animal, this is a very useful tool for identifying your clinically infected animals. You want to open their lower eyelid (use one hand to gently press down on the skin just below the eye and use the other hand to roll down the lower eyelid). You are looking at the inner eyelid, not the eyeball itself. You then check the color and compare it to the FAMACHA chart (see the diagram) and match the color as closely as possible. The whiter the color, the HIGHER the score. This is a common mistake people make when reporting FAMACHA scores. It’s helpful to remember “higher number, higher worm count.”

Here is a video on how to FAMACHA score: FAMACHA Technique Training Video

Body Condition Scoring (BCS)

Body condition scoring (BCS) is done by feeling along their spine just behind the ribs near the lower back. You want to feel the top of the spine and the muscles on either side to assess the level of muscle and fat covering the bones. See the diagram for a visual representation.

Thin (Score 1-2) - If the spine is sharp with concaved musculature and very little covering, they are a thin body condition

Appropriate (Score 3) - If it tapers smoothly down in an upside-down “v” shape, they are of appropriate body condition

Fat (Score 4-5) - If it bulges, they are over-conditioned

Who should I treat?

The animals that should receive treatment are ones that have a FAMACHA score of 4 or 5 or the animals that have a FAMACHA score of 3 AND a body condition score of a 3 or lower. If you have a thin animal, but they have a low FAMACHA score (pink eyelids) the cause of the weight loss is most likely not internal parasites. You should consult your veterinarian on further recommendations for that animal.

Identifying which animals to deworm using FAMACHA and BCS scoring is called “selective deworming” or “targeted treatment” and is the best strategy for treating the animal, preventing future infections and not contributing to drug resistance.

DECIDING WHAT TO TREAT WITH

As a result of decades-long overuse and misuse of dewormers, there is widespread documented resistance. You will need to identify which dewormer your individual population of worms is most susceptible to and avoid overuse, which can lead to a “super bug” resistant to all dewormers and immensely difficult to treat.

Types of Dewormers

There are only three classes of dewormers approved in the US for use in sheep and goats:

Benzimidazoles (Fenbendazole, Albendazole)

Macrocyclic lactones (Ivermectin, Moxidectin)

Imidazothiazoles (Levamisole, Pyrantel, Morantel)

Dosing Dewormers

Because of resistance, the dosing on the packaging is no longer effective. Use the provided two charts (one for sheep and one for goats) courtesy of the American Consortium for Small Ruminant Parasite Control, which provides current recommendations for parasite management in small ruminants and camelids. This organization is an excellent resource, and a link to their website will be provided at the bottom of this guide.

Always make sure you are using an unexpired dewormer that is stored in a cool, dry place out of direct sunlight.

Testing for Resistance (Fecal Egg Count Reduction Tests FECRT)

It is impossible to know which dewormer is effective against the parasites in your animals without testing. This is done through a “Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test” or FECRT. Below are the steps to follow for performing this test:

Identify an animal that requires deworming - FAMCHA score of 4 or 5 or a FAMACHA score of 3 with a low BCS

Give ONE class of dewormer using the dosing guideline chart provided (not the dosing on the bottle)

Collect feces from that animal at time of deworming and submit to the lab. You can usually get the fecal balls directly from their rectum with a gloved hand. You need at least 5 fecal balls.

Mail the feces to the UC Davis CAHF’s lab for a “Fecal Modified McMaster’s Test” test code 10723.

You can refrigerate the feces for up to 3 days prior to shipping.

Ship with an icepack and place the feces in a Ziplock bag and place both the Ziplocked feces and icepack in a larger plastic bag before placing in the box to prevent moisture. The paperwork should be placed in a separate Ziplock back and placed on top inside the box.

Ship the box next day via FedEx, UPS, or similar overnight delivery services. Boxes need to be shipped so they arrive at the lab on a weekday.

The submittal form and instructions can be found here: UC Davis CAHFS Lab

Collect a 2nd fecal sample in 10-14 days from the first and submit it to the lab for another Fecal Modified McMaster’s Test test code 10723.

Compare the 1st and 2nd fecal sample egg numbers.

If the egg numbers in your animal is less than 10% in the 2nd sample compared to the 1st (for example - your animal was shedding 1,000 eggs on the first sample and now is shedding 100 or less after the dewormer 10-14 days later) then your dewormer is EFFECTIVE and you can keep using it.

If your egg numbers are more than 10% in the 2nd sample compared to the first (your animal was shedding 1,000 eggs in the 1st sample and now is shedding more than 100 in the 2nd) then you have RESISTANCE and another class of dewormer will need to be used.

Remember we only have three classes of dewormer and once you have established resistance in all three of those classes, you are out of options for treatment in your animal. If you document parasite resistance in your herd, we recommend seeking veterinary advice moving forward to prevent creating a super bug.

We know this sounds labor-intensive, expensive, and complicated, but it is infinitely easier and cheaper than attempting to eradicate a superbug caused by blindly administering dewormer.

Keeping Refugia - The importance of Genetic Diversity

“Refugia” is a term for the population of parasites not exposed to dewormer. You will never kill all the parasites that live on your property. If you attempt to do this by deworming all the animals at once and rotating dewormers regularly, you will only end up with a “super bug” resistant to all dewormers on the market and impossible to treat.

Remember you are only treating clinically affected animals (high FAMACHA score, low BCS). These are the animals that are at risk of dying and are most likely responsible for shedding the majority of eggs on your pasture. You don’t want to treat healthy animals because they are not sick from the parasite and are maintaining the genetic mix of parasites, all while not contributing to eggs in the environment.

It is helpful to consider that you are not just breeding sheep and goats but also breeding the population of parasites on your land. Every time you use a dewormer, you are killing the parasites susceptible to it and leaving behind the resistant parasites. Resistance to dewormer is a genetic trait, and if the resistant parasites have only resistant parasites to breed with, we will lose our ability to treat sick animals. Maintaining a diverse population of worms that are genetically susceptible to dewormer is extremely important.

TREATMENT PLAN EXAMPLE

Now that we have gone through the “why” for these strategies, let’s tackle the “how.” Below is an example of how to implement the above recommendations for your herd or flock. This treatment plan is only meant as an example and may need to be altered for your individual circumstances. If you have any questions, please reach out to your veterinarian for further guidance.

Divide your pasture into three parcels large enough to prevent over-grazing for the number of animals you have.

Move your animals to the 1st parcel and keep them there grazing for 6-8 weeks.

Three days before you are planning on moving to the 2nd parcel:

FAMACHA and BCS every animal and deworm only the high FAMACHA (4 or 5) or the FAMACHA 3 with low BCS (1 or 2) animals.

Deworm with only one dewormer and use the doses provided in the chart (not the bottle)

Keep complete records:

Date

Animal name or ID number

FAMACHA & BCS scores

If dewormed – type and amount

Collect feces from the animals you dewormed and submit it to the lab for a fecal test (see above FECRT instructions).

Three days later, move your animals to the 2nd parcel. This allows time for them to shed any further eggs before the dewormer kills the parasites.

10-14 from when you gave the dewormer collect feces again on the dewormed animals and submit it to the lab. Compare 1st and 2nd fecal sample egg numbers and perform a Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) to check for resistance (see above for instrucitons).

If resistance is present (failed to reduce 90% or more of the eggs) a new class of dewormer will need to be used next round.

If the dewormer worked (eggs were reduced by 90% or higher), great news! This dewormer is effective and can continue to be used.

Let them graze on the 2nd parcel for another 6-8 weeks.

Three days before you are planning to move to the 3rd parcel:

FAMACHA and BCS every animal and deworm only the high FAMACHA (4 or 5) or the FAMACHA 3 with low BCS (1 or 2) animals.

If you had documented resistance to the first dewormer, you need to use a new class. For example – you used Sheep Drench (Ivermectin) the first go around and it failed to reduce the egg numbers you should now use Safe-Guard (Fenbendazole).

If you did not have resistance you can use the same dewormer.

Compare the animals you are deworming this round with the ones you did a few weeks ago. Are the ones you dewormed before improving (better FAMACHA or BCS scores?). Are you finding you are deworming the same animals again?

Continue to keep diligent records, collect feces and submit it to the lab on the dewormed animals and repeat the fecals in 10-14 days for another FECRT.

Three days later move the animals to your 3rd parcel and let them grave for 6-8 weeks.

Three days before you are planning to move them back to the original first parcel:

FAMACHA and BCS every animal, but BEFORE you deworm, you need to look at the data you have collected over the past few months.

Are you seeing the same animals coming up multiple times with poor BCS and FAMACHA scores?

You should consider removing these animals from your herd (either culling or isolating) since they are most likely shedding 80% or more of the eggs in your pasture.

Have you had documented resistance to dewormers? If you are failing to reduce the number of eggs by at least 90% in two classes of dewormer (remember there are only three classes!) - you are at serious risk of breeding a super parasite capable of resisting all dewormers. Seek veterinary advice moving forward to help prevent this very serious problem.

If you have not had documented resistance or repeat offenders, you can continue to rotate your animals every 6-8 weeks through your 3 parcels.

The above strategy is only meant as an example and you will most likely need to tailor it to your specific circumstances. You can work with your veterinarian to strategize the best course of action for your animals.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

Preventing and treating the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus) requires a strategic approach through pasture management, proper nutrition, and targeted deworming. By using tools like the FAMACHA system and FECRTs, you can reduce parasite burdens while minimizing drug resistance, leading to a healthier, more productive herd or flock.

References

Jones, M. Course 01: Anthelmintic Drug Selection and Use. Large Animal Continuing Education.

Jones, M. Course 07: Herd-Lvel Approach to Small Ruminant Parasites. Large Animal Continuing Education.

Common gastrointestinal parasites of cattle - digestive system. Merck Veterinary Manual. (n.d.). https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/gastrointestinal-parasites-of-ruminants/common-gastrointestinal-parasites-of-cattle?query=barber+pole+worm#Haemonchus-spp-(Barber’s-Pole-Worm,-Large-Stomach-Worm,-Wire-Worm)-in-Cattle_v81479268

UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. (2016, March). Lectures 9, 10, 13: Nematodes 1, 2 & 3; Infectious Disease, School of Veterinary Medicine Curriculum. Davis, CA.

UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. (2017, October). Lecture 13: Small Ruminant Parasite Control; Large Animal Track. Davis, CA.

Related Resources

American Consortium for Small Animal Parasite Control