Backyard Chickens Guide

Backyard chickens make an excellent addition to any small homestead. They are a source of fresh eggs, natural pest control, and aid in a deeper connection to where our food comes from. Raising chickens can be rewarding, but it also comes with caretaking responsibilities that are easy to underestimate. Whether you’re just starting out or looking to improve your existing flock, raising healthy, happy chickens requires a solid foundation of knowledge. This guide to backyard chickens walks you through the essentials, from designing a safe and comfortable coop to providing balanced nutrition and recognizing common ailments before they become serious problems. With the right preparation and care, your backyard can become a thriving, productive haven for your flock.

COOP DESIGN

Many of the common injuries that affect backyard poultry (see bumblefoot and trauma below), can be avoided with a proper coop design. There are countless coop designs out there utilizing a variety of materials. As long as the coop is easy to clean, protects the flock from wild birds and predators, and provides adequate space for them, it will work as an appropriate shelter for your flock.

Location

You want the coop to reside on a portion of your property that is well-draining and slightly elevated. Chickens will quickly turn any patch of grass they are housed on into dirt, so if not properly drained, your flock can end up in a mud pit.

Squatter Proofing

Food and water sources in your coop can attract unwanted residents like wild birds and rodents.

You want to limit your flock’s exposure to wild birds, which can carry disease, cause injury to your birds, or even kill them. Any opening in the coop should be covered with hardware cloth, and any doors should have a screen.

Rodent control is more safely achieved with bait traps. Using rodenticides can be dangerous to your chickens, either through accidental ingestion of the poison directly or ingesting a rodent that has died from being poisoned.

Predator Proofing

You want a coop design that prevents common predators like raccoons, coyotes, opossums, dogs, and birds of prey from entering. To stop predators from digging under the coop to gain access, you can use hardware cloth (which is stronger than chicken wire) to secure the perimeter by burying it about 12-18 inches around the entire coop. If the ground is too hard, you can make a border "skirt” extending outward from the coop 12-18 inches. Any holes or gaps larger than ½ inch should be covered with hardware cloth to prevent small predator entry and reduce the risk of chickens' body parts being pulled through the gaps by predators. To prevent birds of prey, you will want the coop and any runs to be covered, either with a roof, hardware wire, or netting.

Other Safety Concerns

Carefully go through your coop and remove any loose or ragged wire, nails, or other sharp-edged objects. Chickens can snag and injure themselves or eat pieces of scrap wire and metal, leading to illness.

Remove or restrict access to anything that could be seen as another perch or a roosting option to a chicken, like the top of their roost boxes, windowsills, or plugged-in extension cords.

Litter Substrate

There are a variety of litter options out there; however, you want to choose a litter that is absorbent, loose, and has low dust. Each type of litter has its benefits and drawbacks. Common choices are straw, sand, and pine shavings. Straw is cheap and accessible, but not very absorbent. Sand is easily drained and best for foot health (see Bumble Foot below), but it is difficult to keep clean and not very insulating. Hardwood shavings should not be used because they promote mold and can be too aromatic, causing respiratory irritation. Choose a substrate that will allow you to keep your coop design clean and dry.

Perches

Perches are a great way to increase your birds’ exercise, comfort, and natural behavior. They also add extra space to your coop by utilizing the vertical square feet. You want to introduce perches early in life (typically when they are young pullets) so the birds get used to them and understand how they work. You want to place perches away from food, water, and nesting boxes to limit excessive soiling. You will also want to routinely clean out the area below the perches to reduce the accumulation of feces.

Perches can either be made from natural material (like wood), metal, or plastic. Wood perches are easier for chickens to use, but they can’t be disinfected as well as plastic or metal ones and may harbor mites.

Placement of the perches is important to ensure safety for your flock. You want to ensure there is plenty of landing space below the perches, and the lowest perch should be approximately 3 feet off the floor. You want to arrange the perches with minimal vertical distance between them to avoid falls (remember, chickens can’t fly super well!).

Nesting Boxes

You want to introduce nesting boxes to your flock around 4 months of age. If you give access too early, chicks may start to use them inappropriately by roosting and pooping in them. You can line the nest boxes with a variety of bedding, including straw, shavings, or turf grass. You can also choose to leave them bare. Nest boxes should not be used to roost in and should be cleaned out routinely to prevent fecal accumulation.

Temperature

Ideally, you should aim to maintain your coop’s indoor temperature between 50-75°F. Closing windows in the cold winter months and using shade clothes for their runs in the hot summer can help mitigate extreme temperatures. However, chickens are a pretty resilient species and can tolerate temperatures decently outside their optimal range.

Ventilation

Adequate ventilation is important for moisture, excess heat, and irritating gas removal (like ammonia that is produced by urine and feces). Ventilation also provides fresh air and prevents the spread of disease.

Depending on the time of year, you may wish to open windows (make sure they are screened) during the day and close at night to keep the coop a comfortable temperature. Windows located near the roof line of the coop or above roost and nest boxes are most effective. Circulating air fans can also be added to help move stagnant air.

Outdoor Runs

You may want to include an outdoor run space for your chickens to access as well. It is important to have these runs covered both for protection from predatory birds and temperature control with netting, shade cloth, or hardware cloth/chicken wire. You will also want to bury hardware cloth 12 to 18 inches deep or make a 12 to 18-inch apron along the border of the run, similar to your coop, for predator protection.

MANAGING DIFFERENT LIFE STAGES

Chicks

The brooder pen or area should be set up 48-72 hours before chick arrival to ensure all equipment is functioning and allow time for it to warm to an appropriate temperature (start at 95°F and decrease by 5° each week until the outdoor temperature is met). Your brooding area should provide food, water, and heat. Ideally, you set the heat source in the center of the brooding pen and alternate food and water around it to provide baby poultry easy access. A typical heat source is a red light heat lamp. If you see your chicks huddling close together under the lamp, this can be an indication that they are too cold. Alternatively, if they are scattered on the perimeter of the brooding area, this can indicate that they are too hot. Comfortable chicks are evenly distributed throughout the brood area. If they are all excessively chirping, this can also be an indication that they are too hot or cold. You want some chirping, but not all the chicks.

Growing Birds

As chicks grow, their body weight changes, and they start to lose their down, being replaced with feathers. You should refrain from outdoor access until the birds are 6 weeks of age or older (the age when chickens are properly feathered). You can train young poultry to re-enter the coop at night by keeping the lights on for an additional 20-30 minutes past sunset. You might have to help place them back in the first couple of weeks, but they should quickly learn to go in at night.

Molting

Chickens that are producing eggs and are kept for pleasure will go through a molt period. A molt indicates that the hen needs to rest from egg production. You will see her stop laying eggs and start to grow new feathers during this time. You may wish to remove the hen from the flock while she is going through a molt because of her increased vulnerability (see section on conspecific aggression below). A molt period usually lasts about 6 weeks.

Brooding

When hens are “broody,” their hormones change and start to indicate that it is time for them to start nesting and hatching their eggs. When a hen is brooding, she stops laying eggs, identifies a portion of the nestbox as hers, and builds a nest. She may also become aggressive in an attempt to guard her eggs. You can reduce the chances of brooding by promptly removing eggs from the hen house daily. A broody hen should be removed from the flock for a short period to break this hormone cycle, and you should remove her nest and all eggs (hers and others).

CONSPECIFIC AGGRESSION (PECKING ORDER)

Chickens maintain a strict social structure or “pecking order,” which may result in weaker chickens being picked on by more dominant members. Too many birds in too little space is the most common cause. As a general guideline, you want to maintain 3-4 square feet of indoor coop space per bird, and 10 square feet of outdoor space per bird. Large breeds (like Cochin) may require more space compared to smaller breeds (like bantams). Other causes of bird-on-bird violence include incorrect lighting, dietary deficiencies, and prior trauma.

You can reduce this aggressive behavior through environmental enrichment (adding forage opportunities and toys), increasing their living space, and adding more water and feed stations. Individuals with open wounds should be removed from the flock until healed to prevent further picking. You can also use “chicken aprons” to cover the backside of hens to prevent plucking by other members.

NUTRITION

Complete Feeds

Due to their commercial counterparts, nutrition in poultry is an extensively studied subject. However, feeding backyard poultry does not need to be overly complicated. Selecting a complete feed (either mash, crumble, or pellet) specifically designed for the life stage of your chicken is the simplest way to ensure they are getting appropriate nutrition. No additional supplements are needed with complete feeds; however, if you desire, you can provide them with scratch, vegetables, and forage for enrichment and a varied diet. Just be sure the additions don’t cut too much into their intake of the complete feed, compromising the nutritional value.

You want to ensure you are feeding a complete feed designed specifically for the life stage of your flock (it should be stated clearly on the feed’s label). Feeding a diet for the wrong life stage of the bird can result in nutritional imbalances and improper growth. If you are feeding laying hens, the complete feed should contain 2.5-3.5% calcium. You can offer additional calcium free choice (in a separate container from the complete feed). Oyster shells, calcite, and limestone are great options for supplemental calcium.

They will need access to fresh feed daily. The feed should be stored in a cool, dry place in a rodent-proof container (such as a 5-gallon bucket with a screw on lid). You also do not want to store your feed for long periods of time because this leads to degradation of vitamins. Keep track of expiration dates and ideally, you should only purchase enough feed at a time that can be consumed within 30 days. This will ensure nutritional content and reduce the chance of spoilage.

Water

Ensure that water containers cannot be spilled or soiled throughout the day. Consistent access to fresh, clean water is key to a healthy flock. Water containers should be scrubbed regularly with soapy water to remove dirt and bacterial buildup.

Grit

Hard, insoluble granite grit should be offered in a small dish 2-3 days per month. This helps aid in their digestion. They will also pick up small stones and sand to achieve the same result.

DISEASE PREVENTION

Most diseases in backyard chickens can be averted by practicing good hygiene, biosecurity, and preventative care. Disease can spread quickly through a flock, so reducing your birds’ exposure to diseases in the first place and maintaining an unfavorable environment for bacteria and parasites is a great strategy for maintaining a resilient, productive flock.

Quarantine

Quarantining new birds is essential in keeping your established flock healthy, and is often not practiced by backyard poultry owners, leading to devastating outcomes. Newly purchased birds should be quarantined for 30 days prior to introduction into your existing flock. During this quarantine period, new birds should be screened for common diseases. Feces and blood should be collected for internal parasite and disease testing (like Mycoplasma), and birds should be thoroughly examined for evidence of lice or mites (see external parasites below).

If any signs of disease are seen during that time (diarrhea, sneezing, lethargy, etc.), appropriate diagnostic tests should be performed. If signs of disease are seen in one of your existing flock members, they should immediately be separated until testing and treatment are pursued. Consult with your veterinarian for further recommendations on testing, treatment, and disease prevention.

Quarantining does not just apply to new birds, but also to birds that leave the property for any reason (like a fair or show). These birds should be kept separate for 2 weeks before incorporating them back into the flock.

Biosecurity

In addition to quarantining new arrivals and sick birds, other biosecurity measures should also be implemented to greatly decrease the occurrence of disease in your flock. Avoid direct contact between your flock and wild birds (especially migratory waterfowl). All equipment should be routinely cleaned, including your shoes and clothing. It is best to avoid sharing equipment or allowing neighbors who also have backyard flocks to interact with your chickens. Used litter should be disposed of properly in an area inaccessible to other poultry, predators, or pets.

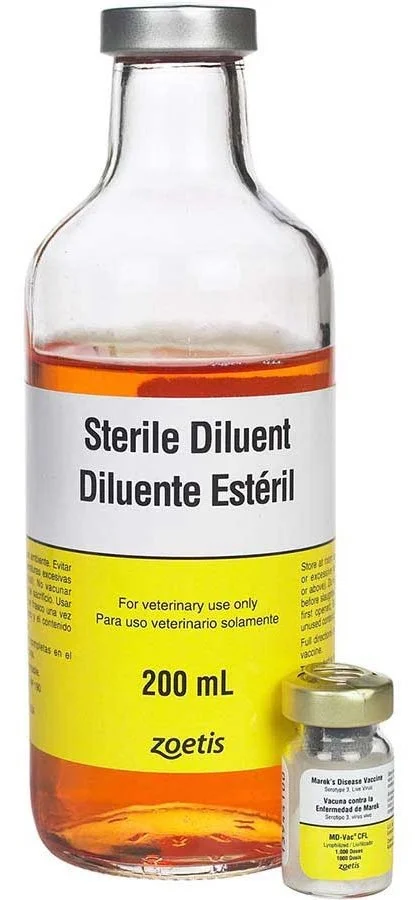

Vaccinations

Most vaccines are not easily utilized by backyard flock owners because they come in very large commercial quantities (1,000 doses) and have extremely short shelf lives once opened (usually 1-2 hours). Furthermore, vaccinating birds is technically challenging because the chick needs to be vaccinated while they are still in the egg or within the first few days after hatching. Obtaining chicks that are already vaccinated is a much more feasible strategy for the average backyard flock owner.

You want to ensure you are purchasing birds that are already vaccinated for Marek’s Disease (see more information on Marek’s Disease below). Marek’s Disease is endemic in this area of California, and unvaccinated chicks from the feed store or breeder, or chicks born on your property, are at extremely high risk of contracting the disease and dying at a young age. Chicks that are vaccinated for Marek’s Disease will be clearly stated as such when purchasing.

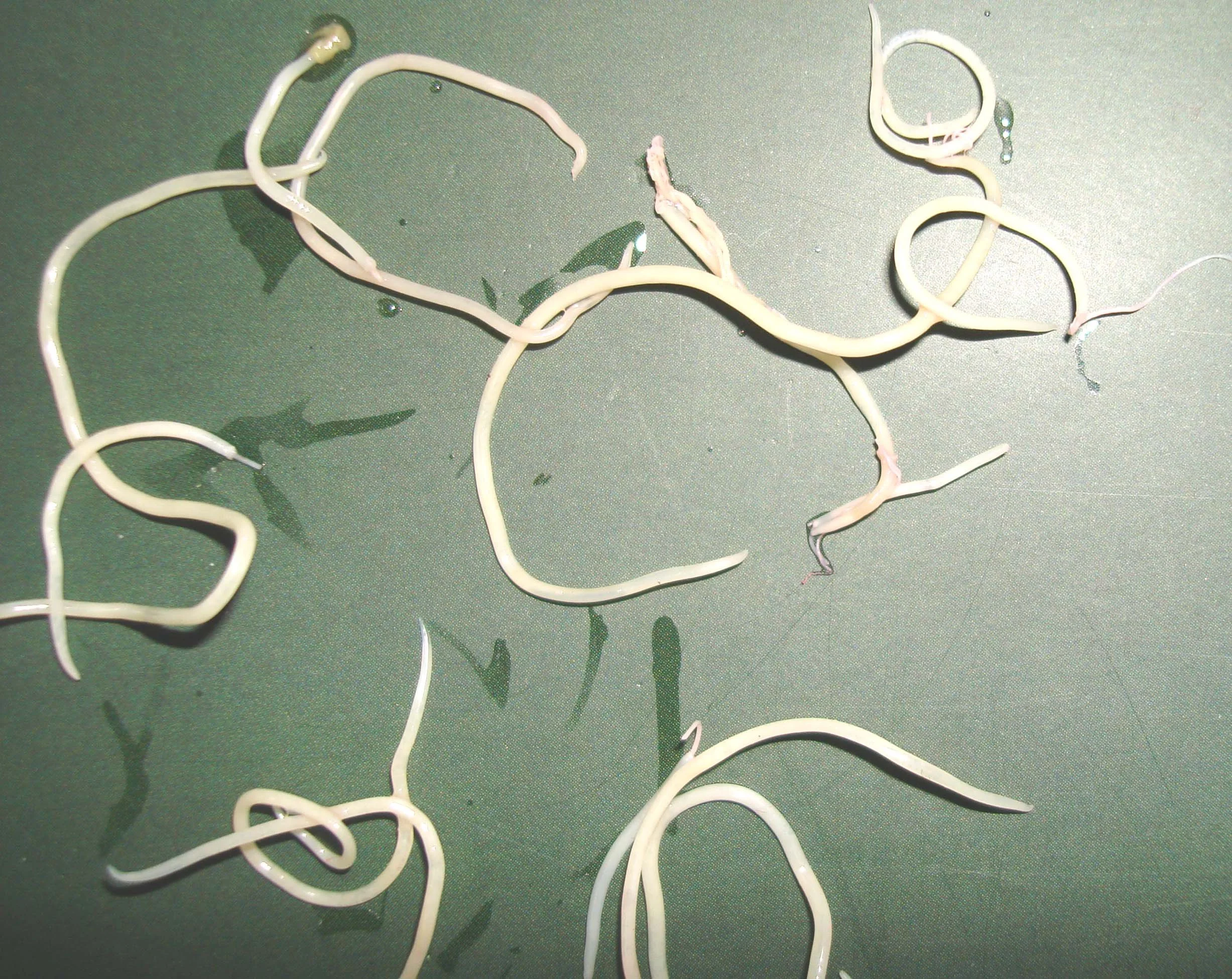

Internal Parasite Control

Internal parasite infections are inevitable in backyard poultry. You will never completely eliminate all parasites from your free-ranging flock, and attempting to do so will lead to birds sick with parasites that have developed resistance to the available medications making them incredibly difficult to treat. A more effective strategy is to monitor and manage your flocks’ parasite load. This is achieved by identifying the parasites your flock has through routine flock fecal tests (typically performed every 6 months, ideally late spring and late fall) and treating individual birds when clinical signs arise based on those results.

RECOGNIZING DISEASE IN YOUR CHICKENS

Because chickens are a prey species, they are incredibly stoic, often not showing any signs of clinical disease until they are too sick to no longer hide it. Also, regardless of what is wrong with them (from internal parasites to respiratory disease, to reproductive cancer), they typically show the same clinical signs of general depression: isolating from the flock, fluffed-up feathers, weakness, loose stool/staining around their vent, open mouth breathing, and weight loss.

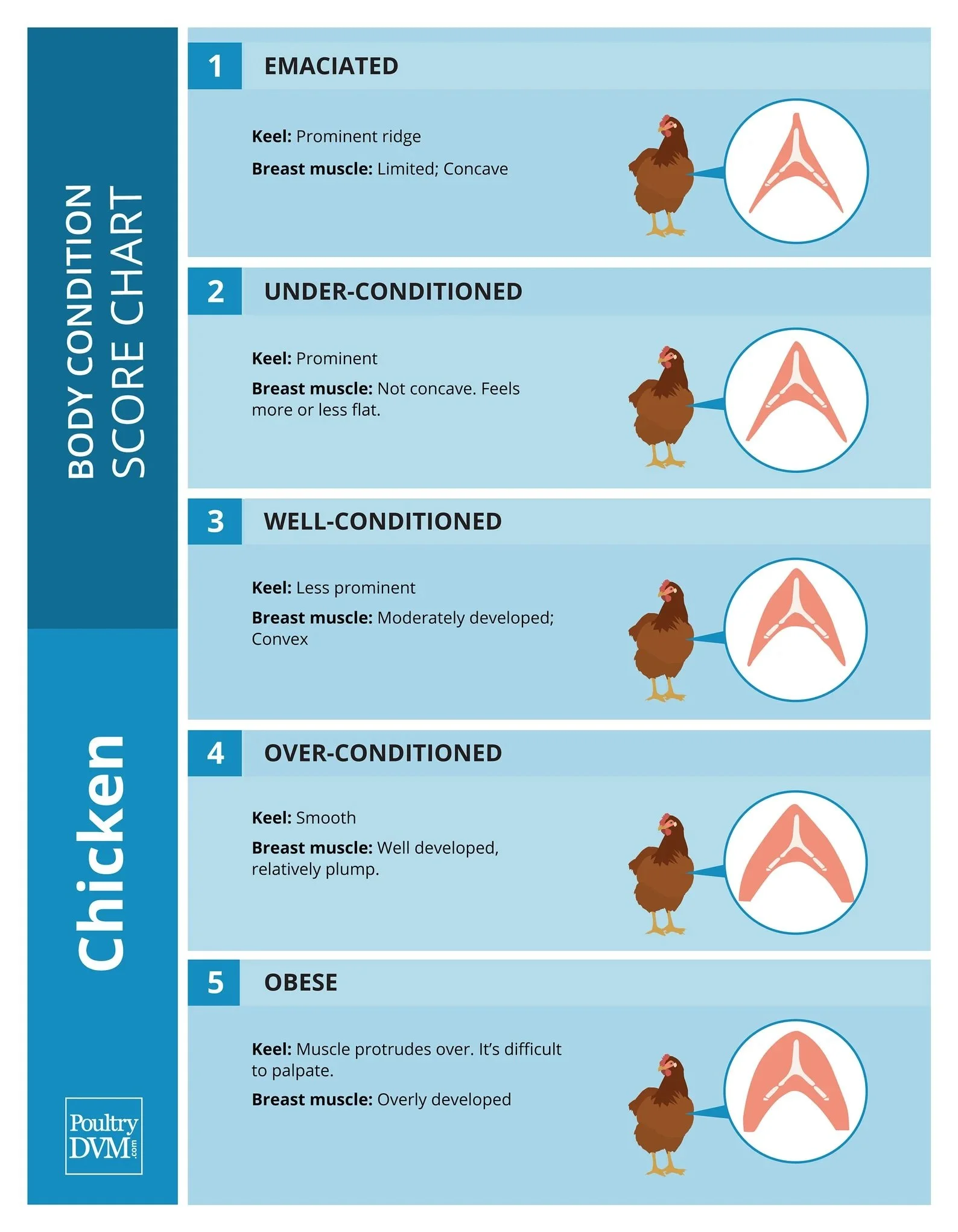

Weight loss is typically the first sign there is something wrong with your chicken, so routinely body condition scoring your flock (see chart to the right), by feeling the muscle on either side of their keel (the bony line on the front of their chest), can help identify early signs of illness.

If signs of disease are seen in your birds, please isolate the bird (both to prevent spread of infection and prevent injury from other birds picking on them) and please seek veterinary care immediately. Even if you have only seen the bird sick for one day, it most likely has been going on much longer than that and if the bird is showing outward signs of illness they are very sick.

INTERNAL PARASITES

This section will cover some of the more common internal parasites that affect backyard flocks. This is by no means a complete list, and if you are concerned your flock might be infected with one or more of these parasites, we recommend consulting with your veterinarian for further guidance on treatment and management.

Coccidia (Eimeria)

Pretty much every backyard flock is exposed to coccidia (Eimeria). This is a protozoal parasite (a single-celled microscopic organism) that lives in the lining of the chicken’s small intestines. Typically, chickens do not have any signs of illness unless they are infected with a large number of coccidia. When they become sick from coccidia they usually have general signs of illness like decreased energy and appetite. This parasite is spread through the ingestion of feces containing the parasite’s eggs. Promptly removing feces and maintaining a clean coop environment is the best strategy for preventing infections and clinical disease of coccidia. If you have an individual bird that is showing signs of illness (fluffed feathers, weight loss, depressed, not eating well), please consult your veterinarian for the best treatment strategy. Over-medicating and over-treating for this parasite, including using preventative treatments, can interfere with your flock’s natural immunity they build to this organism, leading to a sicker, less resilient flock.

Worms (Helminthiasis)

There are several types of worms that infect backyard flocks. Roundworms (nematodes) like Ascaridia galli and Ascaridia dissimillis, the cecal worm Hetarakis gallinarium, the threadworm Capillaria, and the gapeworm Syngamus trachea are commonly seen on routine fecal testing in backyard flocks. Chickens become infected by eating the parasite directly or by eating something delicious like an earthworm, snail, or slug that has ingested the parasite. Clinical signs for these worms include the general signs of illness in chickens (depressed, weight loss, decreased appetite), and in the case of Capillaria and Syngamus trachea, you might also see open-mouth breathing. Again, you do not want to treat your entire flock with dewormer, only individual sick birds. You can add diatomaceous earth to your flock’s feed (2% in their feed and fed continuously), to reduce the overall worm population in your flock without contributing to dewormer resistance. If signs of illness are seen in one of your birds, please consult your veterinarian for further recommendations.

EXTERNAL PARASITES

External parasites such as mites and lice are common in backyard poultry. Identifying infestations early by routinely checking your flock and coop can help prevent a larger flock outbreak.

Mites

Mites feed on blood, feathers, and skin, and are very tiny but can be seen with the naked eye. Some mites spend their entire life on the chicken, while others hide in the environment during the day (like the Red Chicken Mite), so treatment requires treating the environment as well as the bird. Common species of mites in backyard poultry include the Red Chicken Mite (Dermanyssus gallinae), the Northern Fowl Mite (ornithonyssus sylvarium), and the Scaley Leg Mite (Knemidokoptes mutans).

As previously stated, the Red Chicken Mite can be difficult to see on infected birds because they feed on chickens at night while they roost, and during the day, the parasite hides in the coop. These mites usually hide in tight corners and crevices in your coop, so look for them there. Signs that your chicken is infected with Red Chicken Mites include depression, skin irritation, itchiness, and pale combs.

The Northern Fowl Mite lives on the chicken at all times, and the bird can become infected by exposure to contaminated objects (crates, cages, etc.) or wild birds. Infected birds will have soiled feathers around their vent, tail, and rear legs. You will also commonly see these mites on the eggs.

The Scaley Leg Mite spends its entire life on the chicken, and birds are infected by direct contact with other infected birds. They infect the tissue under the scales of the legs and feet, leading to thick, crusty legs and feet with raised scales. Severe cases can lead to twisting of their nails, discolored/dead toes, and lameness. “Pants-wearing” chicken breeds like Silkys and Cochin’s are most at risk. Specific treatment for these mites includes smothering them with petroleum jelly applied directly to the legs daily or Ivermectin.

Treating individual sick birds with Ivermectin has been shown to be effective; however, if the environment is not also cleaned and treated, the bird will eventually be reinfected. Thorough cleaning of the coop and the use of environmental insecticides are the best strategies for treatment and prevention of this mite. Tetrachlorvinphos and Dichlorvos have been shown to be the most effective, followed by Malathion dust and 10% garlic oil. Providing your flock with dust boxes (either with diatomaceous earth, kaolin clay, or sulfur) has also shown to greatly reduce mite numbers. Boxes containing sulfur showed ongoing effectiveness up to 9 months after the boxes were removed.

Lice

Lice live their entire life on the bird and chewing lice (not blood sucking lice). They chew and eat the feather debris, skin fragments, and feather shafts. They are easily seen by the naked eye and you will find them where they like to dine: at the base of the birds’ feathers (especially around their vent, inner thighs, armpits, and tail base). Infected birds will have inflamed skin, small scabs, and a moth-eaten appearance to their feathers. Birds become infected with lice through exposure from other infected birds. Treatments include Ivermectin (although efficacy is debatable), and providing diatomaceous earth dust baths (which have been shown to be effective).

TRAUMA

Trauma from predators, other flock members, or accidents is a common occurrence in backyard poultry. Chickens are amazing healers when given timely treatment; they can often recover from most wounds and bone fractures. If injuries are seen, please separate the chicken (to prevent further injury by flock members) and seek veterinary care immediately.

RESPIRATORY DISEASE

Symptoms of respiratory disease in chickens include increased respiratory rate and effort, audible noises when breathing, sneezing, open-mouth breathing, and stretched out necks. You might also see swelling of their sinuses which will be located around their eyes. General signs of a sick bird also apply: quiet attitude, weakness, and weight loss.

There are several infectious respiratory pathogens in poultry that can cause disease ranging from mild clinical signs to sudden death of several flock members. Below is a brief description of some of the more common respiratory diseases in backyard flocks, but this is by no means a complete list. If you are concerned that your flock might be dealing with a respiratory disease, please consult your veterinarian for further advice, treatment, and testing recommendations.

“Weather-Related” Respiratory Disease

This is probably the most common cause of respiratory disease in small backyard flocks. When the weather changes in the spring or fall, some chickens will develop audible rattling when they breathe, snicking (reverse sneezing), sneezing, and sometimes coughing. The birds are otherwise doing well with normal energy levels, appetite, and are keeping up with the flock.

There is no specific cause of “weather-related” respiratory disease, and it is usually attributed to changes in the birds’ local environment (temperature change, moisture change, increase in dust or irritants like ammonia from urine and feces), which causes a change in the bacteria that normally reside in their respiratory tract, leading to illness.

Most of these birds do not require treatment, and the condition will resolve on its own; however, if you see your bird start to show more serious signs of illness (isolating from the flock, weight loss, weakness) this is a sign that something more serious is going on and requires veterinary attention.

Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma is everywhere, and many backyard poultry flocks carry some degree of it. It causes chronic respiratory disease symptoms like sneezing, nasal discharge, and swelling of the sinuses. These symptoms may worsen with additional infections from other bacteria. Your veterinarian may prescribe antibiotics to treat sick birds and help alleviate illness, but it is important to realize that there is no treatment or cure for Mycoplasma; once a flock is infected, they have it forever.

Maintaining a Mycoplasma-free flock by buying only certified Mycoplasma-free birds, and through good biosecurity and quarantine practices, is the most effective defense against Mycoplasma.

Fowl Cholera (Pasteurella multocida)

With Fowl Cholera, you will see swollen eyes, waddles, and ears, general signs of respiratory disease, and death in several birds. It is spread from bites from cats and rats, who carry this bacteria as a normal inhabitant of their mouths. Antibiotics may reduce the number of deaths, but it will not cure them of the disease, and once infected, the flock will always carry it.

Infectious Laryngotracheitis (Gallid herpesvirus 1)

The clinical signs of Infectious Laryngotracheitis are generally dramatic, with bleeding from the mouth and several deaths in the flock. Usually, the disease will manifest about 7-10 days after the addition of new birds or birds that have returned from a fair or show. This disease occurs typically when unvaccinated birds are mixed with birds vaccinated for Infectious Laryngotracheitis. The vaccinated birds carry the disease and transmit it to the unvaccinated. This disease stresses the importance of quarantine and biosecurity. There is no treatment for Infectious Laryngotracheitis.

Infectious Coryza (Avibacterium paragallinarum)

Respiratory signs, eye and nose discharge, swelling of the sinuses, and sudden death are common occurrences with Infectious Coryza. It is spread through the air, ingestion, and people’s clothing. If the disease is caught early, having your veterinarian flush the sinuses and administer antibiotics might be effective; however, most cases are very serious and require euthanizing affected birds and completely disinfecting their environment.

Avian Influenza

State and federal officials closely monitor two types of avian influenza based on their ability to cause disease in poultry: low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) and high pathogenicity avian influenza (HPAI). LPAI naturally occurs in wild birds and can spread to domestic poultry, typically through inhalation of the virus, contact with contaminated equipment or feed/water bowls, or ingestion of feces from infected birds. Once in domestic poultry, Avian Influenza has the potential to mutate to the HPAI strain, which can cause serious illness and even death in other species, including humans.

HPAI is of great concern, and although most HPAI viruses have been associated with conjunctivitis or mild influenza-like illness among people, some viruses are capable of causing severe or fatal illness. Human infection with the Avian Influenza virus occurs mainly after close contact with poultry. HPAI can also be found in poultry meat and eggs; however, proper cooking will inactivate the virus and make the products safe for consumption. If you have further concerns regarding your own health and your potential risk of avian influenza, please consult your medical doctor.

The likelihood of Avian Influenza occurring in backyard flocks is relatively low. For your flock to be at risk, there needs to be an opportunity for your flock to come in close contact with wild migratory waterfowl. If your chickens are located near a body of water where migratory waterfowl congregate, they are more at risk of Avian Influenza infection. Clinical signs of Avian Influenza range from mild respiratory signs seen with the LPAI strain, to very serious, sudden disease and death with the HPAI strain. If you are concerned your flock may be infected with Avian Influenza, please contact your veterinarian immediately.

Newcastle Disease

Similar to Avian Influenza, Newcastle Disease has the potential to cause a wide range of clinical signs from mild respiratory, depression to sudden death dependent on the strain the bird is infected with. Chickens usually become infected by exposure to other poultry, but wild birds can also carry it. If you are concerned your flock may be infected with Newcastle Disease, please contact your veterinarian immediately.

REPRODUCTIVE ISSUES

“Egg-Bound”

Egg-bound chickens will have stopped laying, have issues walking, and there usually is an egg in their cloaca. If you are concerned your chicken is showing signs of egg binding, please consult your veterinarian for further assistance.

Causes of egg binding include an excessively large egg (double yolk), low calcium, trauma to the vent (usually from pecking from another chicken), or obesity. Regularly monitoring your birds’ body conditions, preventing obesity, feeding adequate calcium (see the “nutrition” section above), and preventing vent trauma (see the “conspecific aggression” section above), are all good strategies for reducing the occurrence of egg binding in your flock.

Cloacal (Vent) Prolapse

Tissue protruding for your chicken’s vent is a medical emergency, and you should promptly remove the bird from the flock (to prevent further trauma from other birds), and seek veterinary care immediately if seen.

There are several causes of prolapses, including trauma (from a fall or pecking from another chicken), a mass in the abdomen (usually cancer of the uterus or gastrointestinal tract), nutritional deficiencies, excessive parasites, or other underlying health conditions.

Reproductive Cancer

Reproductive cancer is very common in chickens and is the leading cause of death in backyard poultry. Approximately 35% of chickens over the age of 2.5 years have reproductive cancer. Symptoms usually go unnoticed until the chicken is in the late stages of the cancer, and the signs are vague and non-specific – weight loss, reduced appetite, depression, isolating, reduced or abnormal egg production, and/or abdominal distention. Treatment options for reproductive cancer are incredibly limited. Removal of the cancer (salpingohysterectomy) is a very high-risk surgery, and due to the typical advanced stage of the cancer when first diagnosed, humane euthanasia is often recommended.

CROP ISSUES

Pendulous “Dropped” Crop

When the crop expands beyond its normal size, the tissue can be irreversibly stretched, leading to an enlarged, drooping crop.

Any condition that interferes with the crop emptying can lead to a pendulous crop. This interference can be a physical blockage: the bird has eaten an inappropriate item (large rocks, grass clippings, strings, feathers, other foreign material), that has become lodged in the crop. Physical obstructions can usually be managed with surgical emptying of the crop. Blockages further down the gastrointestinal tract can also result in a pendulous crop. A blockage in the stomach or small intestine will eventually back up into the crop, where we will be able to see the distention. It is important to realize that an enlarged crop can be caused by an obstruction located in any segment of the gastrointestinal tract and is often not a specific crop issue.

If you see enlargement of your chicken’s crop, please seek veterinary attention for proper treatment. Never attempt to “dip” your bird by holding them upside down and massaging their crop in an attempt to get them to regurgitate. This practice is very dangerous, and your chicken is at a high risk of aspiration pneumonia.

“Sour Crop”

A “sour crop” is when a chicken has a sour odor to their breath, foul-smelling regurgitation, and a distended crop. A sour crop is caused by a bacterial and/or fungal infection within the crop; however, this infection of the crop is usually not the actual cause of the illness but rather a condition that resulted from a larger, more underlying disease process in the chicken.

LAMENESS

“Bumble Foot” (Pododermatitis)

Bumble Foot looks like dark, round, painful scabs on the bottom of their feet. It is caused by a cut or scrape on the foot that becomes infected (usually with Staph), which leads to a circular-shaped, painful sore that may or may not cause your bird to limp. Large breed chickens, obese chickens, and chickens that walk on sharp, hard ground like gravel are most at risk.

Minor cases of Bumble Foot can be treated by encouraging drainage and softening of the scab. You can soak their feet in warm Epson salt water for 15 minutes once or twice a day to soften the scab. Using an over-the-counter keratin softening product like Dr. Scholl’s Liquid Corn and Callus Remover after soaking can also help. If the scab is very painful, the bird is limping, or there is foot or joint swelling, these cases are more serious and a veterinarian should be consulted for further care.

Using soft substrate, like sand, in their runs, encouraging exercise, and maintaining an appropriate weight are good strategies for the prevention of Bumble Foot.

Slipped Tendons (“Perosis”)

A potential cause of a leg that is stuck projecting away from the body and has an enlarged hock joint is a slipped tendon (the gastrocnemius tendon). This is caused by deficiencies in choline, manganese, and biotin which is very rare in chickens that are fed a complete feed. If you are concerned your bird has a slipped tendon please consult your veterinarian for further treatment.

Mycoplasma

Along with causing chronic respiratory disease in backyard flocks, Mycoplasma can also cause lameness. Clinical signs of lameness caused by Mycoplasma include swollen joints (usually the hocks and foot pads). Treatment can be attempted with antibiotics, but once birds are infected they remain carriers for life.

Septic (Infected) Joints

There are many possible causes of a septic joint, but the most common bacteria are Staph, E. coli, and Salmonella. These bacteria gain access to the joint either through a break in the skin (usually trauma), or the bird becomes systemically ill, and the bacteria gain access to the joint through the bloodstream. The bird is lame and one or multiple joints are swollen and warm. Treatment is difficult, requires long term therapy, and there is an overall poor prognosis for the bird’s quality of life.

Marek’s Disease

Marek’s Disease is very common in backyard flocks. The virus has the ability to infect a variety of different tissues in chickens, which means it can cause a wide range of clinical signs including lameness, complete paralysis or rigid outstretching of one or both legs, flaccid necks, muscle tremors, depression, eye color changes (become gray), off-feed, diarrhea, pale drooping combs, weight loss, vent prolapses, and sudden death. Usually, clinical signs are seen in younger chickens (less than a year old). Most birds infected with the virus die, and the ones that survive usually have some degree of chronic illness (like lameness or muscle tremors). The survivors will also shed the virus for the remainder of their lifetime.

Marek’s disease is ubiquitous in this region of Northern California, and virtually all chickens will be exposed to it in their lifetime. It is highly contagious, spreading through the air, direct contact with infected chickens, or contact with contaminated equipment and feeders. Studies have shown that it can survive in the environment for at least 10 years. Once birds are infected, they shed the virus forever.

Due to the nature of this virus, limiting your birds’ exposure to Marek’s Disease is not a feasible strategy for preventing disease and death; they need to be vaccinated. The vaccine is designed for production flocks, not backyard owners, so vaccinating your own birds, while possible, is complicated. Chicks need to be vaccinated either while still in the egg or at 1 day of age, which makes the vaccine technically difficult to give. It is also sold in very large quantities (usually 1,000 vaccines per bottle), and has a very short half-life once opened (about 2 hours). Instead of attempting to vaccinate your own birds, we recommend always purchasing birds that have already been vaccinated at the hatchery; it will be clearly stated when buying the birds. It is important to keep in mind that no vaccine is 100% protective, and the Marek’s vaccine that’s on the market only protects against one of the three strains (although there is some cross-protection), so there is still a possibility a vaccinated bird could become sick with Marek’s Disease. Also, vaccinated birds shed and carry Marek’s Disease, so if you have non-vaccinated birds in your flock, they can be exposed and become sick if introduced to vaccinated birds.

CHICKEN NECROPSY (ANIMAL AUTOPSY)

If you've lost a chicken and want answers, sending it to the California Animal Health & Food Safety Lab (CAHFS) at UC Davis for a necropsy (animal autopsy) is a smart move that can really benefit your whole flock. Not only will you get detailed information about what caused that individual bird's death, but the findings can help identify potential risks (parasites, nutrition, contagious diseases) that might affect your other chickens. It is a valuable tool for prevention and flock health management, and you might be surprised how much insight one bird can offer. Think of it as turning a loss into knowledge that protects the rest of your flock. Never put deceased birds in the freezer; only refrigerate. Freezing damages the tissues and affects test results. Sending animals to the lab for necropsy sounds expensive, but this service is specially provided for backyard flock owners ($35 per two chickens).

If you have several sudden deaths in your flock at once, this is highly concerning and requires immediate contact with a veterinarian. Do not move birds off the property or send birds to the lab until instructed to do so.

The submission form and submission/packaging requirements for shipping deceased birds can be found here – UC Davis Backyard Poultry Submission Guidelines.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

A well-designed, clean, and predator-proof coop lays the groundwork for flock safety, while proper nutrition, fresh water, and good hygiene support long-term health and productivity. Understanding normal chicken behavior and looking for subtle changes is the first step to early recognition and management of disease. By prioritizing biosecurity, managing disease risks responsibly, and working with a veterinarian when problems arise, you set your flock up to thrive. With these tools, backyard chickens can be not only productive but also resilient, healthy, and deeply rewarding members of your homestead.

REFERENCES

Greenacre, C. B., & Morishita, T. Y. (2021). Backyard Poultry Medicine and Surgery: A guide for veterinary practitioners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Savo, Paige. Course 88: Practical Preventive Care for Backyard Poultry. Large Animal Continuing Education.

Savo, Paige. Course 89: Five Common Presenting Conditions for Backyard Poultry. Large Animal Continuing Education.

UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. (2019, May). Poultry Medicine Elective. School of Veterinary Medicine Curriculum. Davis, CA.

USDA-APHIS National Veterinary Accreditation Program Supplemental Training. (2025, February). Module 18: Avian Influenza & Newcastle Disease.

RELATED RESOURCES